|

|

|

|

|

Divided Halves

I, the divided half of such (Alfred, Lord Tennyson, 1809-1892) Warning: This is about the passage of time, which in the nature of things means that in the course of it major characters die. On the other hand, for reasons which will become clear, I don't think of it as a "death" fic as such. AU for "Return of the Man from UNCLE". I also assume that Alexander Waverly was about ten years younger than Leo G. Carroll; those who prefer to assign the characters the same birth date as the actors who portray them are welcome to assume that Waverly simply lived to an exceedingly ripe old age.

She, she is dead; she's dead; when thou know'st this, (John Donne, 1571?-1631) Illya took the steps two at a time and put on a last spurt just before his shoulder collided with the door at the top. The momentum was far more than the weak lock could withstand and the door burst open, spilling him onto the roof. He only lost his balance for a moment, but in that fraction of a second, the split second between “not ready” and “ready”, between “before” and “after”, between “then” and “the rest of my life” he heard a gun fire, and then another, and as he regained his footing he saw Napoleon fall backwards off the edge of the building. It wasn’t anything like a movie. Napoleon didn’t clutch his chest or freeze for a moment, outlined against the New York skyline. The force of the bullet simply knocked him over the edge and he was gone, as quickly as a pebble dropped into water and with the same lack of drama. Illya had to turn his attention back to the man with the gun – to both men with guns, for there proved to be another one lurking in the shadows – but as soon as they had been dealt with he ran over to the edge and looked down. It was too dark to see anything much, but already he could hear an ambulance siren above the noise of the traffic and soon he could make out the blue and red flashing lights. He went down the stairs far more slowly than he had come up. It was a delaying tactic, a way of putting off the inevitable, for eventually he had to reach the bottom and be told officially what he already knew.

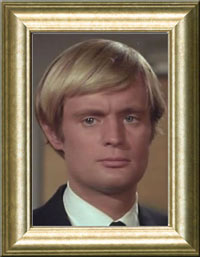

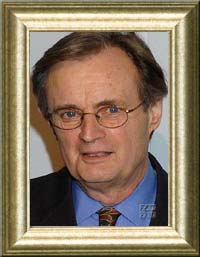

10 November 1969 (Elsa) Come what come may (William Shakespeare, 1564-1616) I'd only been working at UNCLE for a couple of weeks when Napoleon Solo was killed, but you could tell he'd been a popular guy because the whole of HQ reacted as if it was JFK all over again. I'm sure half the girls in the typing pool were wearing black underwear in his honor, and the other half were regretting that they had no reason to. The only one who didn't seem that affected was his partner, Mr Kuryakin. He even came into work the very next day, as tight-lipped and unfriendly as ever. The other girls were sure he was secretly heartbroken, and there was lots of discussion of ways to comfort him, but I'm not so sure. It's not as if he was grateful for any of this attention. When anyone expressed their regrets he just nodded curtly and moved off. He looked equally indifferent at Solo's funeral, if a little pale, and though he was quite happy to have a long talk with Mr Waverly after the service, he was too stuck up to even say hello to anyone lower down in the ranks. I know for a fact that Mr Waverly offered him compassionate leave, but he wouldn't go. He just hung around HQ, mostly locked away in his office but occasionally venturing down to the commissary to fetch a coffee and bring all conversation to a halt. It made it very hard on everyone else. They all felt sorry for him, obviously, because it's a terrible thing to lose a partner, one of the worst things that can happen to a field agent, but on the other hand they were all missing Napoleon as well, and it wasn't made any easier for them by having Kuryakin hanging around like the Ghost of Christmas Past. It was quite a relief when Waverly sent him back into the field, on what Lisa Rogers, in a surprising burst of (over-) sensitivity, firmly instructed us not to refer to as "solo missions." After that he was teamed up with a couple of rising talents from Section 2, but things didn't go all that well. Apparently Waverly said it was down to "a series of unfortunate coincidences", which is Waverly-speak for bad luck. Maybe Kuryakin needed Napoleon's legendary good fortune to counterbalance his own evident lack of it, or maybe he's not such a great agent as everyone thinks when Solo's not around to bale him out. Or maybe he just didn't get on with the men he was teamed with. It's not that Kuryakin has an abrasive personality, more that he doesn't have a personality at all. Maybe that's why he's supposed to be such a good field agent. Most of those guys have some kind of mask that they put on to disguise their real selves, a larger than life persona that's extravagantly exuberant, or charming, or foolish, to distract from their real purpose, but Kuryakin is such a grey mouse that no-one ever notices him anyway, in spite of his really rather striking looks. He'd make an excellent serial killer, the kind where the neighbours say "He was always so polite," and never notice that for thirty years he's been slicing up young ladies in the cellar next door. Not that I think Mr Kuryakin is really a serial killer, I hasten to add. In fact, when he came back from his most recent mission, which had been quite successful, I thought maybe we could bury the hatchet and congratulated him. He gave me a look - those Paul Newman eyes are so wasted on a man like that - and said "You mean congratulations on not getting anyone killed this time." He didn't sound like he actually cared; he just wanted to put me on the wrong foot, so you can see that the news of his defection didn't exactly break my heart. Well, "defection" is Waverly's word for it, but really he's only transferred to Intelligence, and I can't see why everyone else is so upset about it. He'll still be in the building for those girls who are wedded to the conviction that all he really needs is someone to mother him, and those of us who are less keen won't have any more contact with him than typing up his reports. He's much more the sort for a desk job, anyway.

2 February 1995 His golden locks time hath to silver turn'd; (George Peele, 1558?-1597?) Illya had never been a man with an active social life and as he grew older his natural inclination to solitariness became a fixed habit. Nevertheless, he made a point of visiting Alex Waverly in the nursing home at least once a month. Waverly had intended to spend his declining years in England in what he referred to as “the ancestral pile”, but he had deferred retirement for so long that his wife had died while he was still at UNCLE, and without her he felt no particular urge to return to a homeland that had long since become foreign to him. He had stayed on in America, and at UNCLE, disgracefully long past retirement age, until a fall put him into a wheelchair and then into a home. Illya suspected that their common experience of being expatriates had drawn them closer as they grew older, not to mention their shared reputation for curmudgeonliness and their conviction that no-one else could possibly do their job half as well. Normally they talked about work – Illya’s, unless Waverly was indulging in reminiscences – or politics. Illya found it a relief to have someone he could talk to freely about his increasing disillusionment with his job. “It was different in your day, Alex,” he said morosely, “Back then UNCLE stood for an ideal. The ideal of enforcing the law for all nations, regardless of their military clout or economic significance. Now we’re just America’s rottweiler and law means US national interest. I’m not sure how much longer I can keep it up.” Waverly shot him a glance that had lost none of its sharpness over the years. “This sounds more serious than usual,” he said. “I’m accustomed to pessimism from you, but this seems suspiciously like quitting.” “Would that be such a bad thing? According to UNCLE policy I'm due to retire in two years' time. At the latest.” “UNCLE policy has always been to make an exception in exceptional cases,” said Waverly. “They need you, Illya, and you know it. Now, perhaps, more than ever.” “They may need me, but I’m not sure I like what I’m needed for,” said Illya, sinking further into gloom. “I used to be part of the solution, Alex. Now I’m starting to feel like I’m part of the problem. Where did it go wrong? Glasnost, an end to the war in Afghanistan, detente in the Middle East, the demise of Thrush – and now it turns out that all it did was remove the checks and balances. UNCLE used to help maintain equilibrium; we evened things out for the underdog. Now we justify the behaviour of the overdog.” “I can’t say I disagree with your assessment,” said Waverly drily. “But are you sure quitting is the answer? Why not use your position to fight back, to restore UNCLE to what it was? After all, it’s better to light a candle than to curse the darkness.” “I’m an old man,” said Illya, ignoring Waverly’s suspiciously homespun-sounding wisdom. “I don’t have the energy to change the course of history. And even if I had the energy, I wouldn’t have the time. How many years of activity have I got left? Five? Ten?” There was a long silence. Preoccupied with his thoughts of mortality, Illya barely noticed that Waverly wasn’t holding up his end of the conversation, until the old man pivoted his wheelchair and made his painful way to the bookshelf. He fussed inefficiently about the shelves for a while before plucking out a large book and coming slowly back to the table. Illya knew better than to offer him any help, so he merely sat and watched until Waverly set the book down before him with a bang and said “I wanted to show you this before you made up your mind.” It was a dark blue hardback, the size of a large photo album, with no title on the cover. His curiosity provoked, Illya opened the first page. A black and white photo of a young man smiled back at him. His hair was very short, with a side parting, and he was wearing a tweed jacket, with a pipe clenched between his teeth. All the signs pointed to the picture having been taken in the 1950s. Above the photo a small piece of paper had been glued onto the page bearing the words “Jack Phelps” in old-fashioned typewriter print. Below the photo was what looked like a résumé, in Waverly’s oddly elegant scrawl. Having had years of practice in deciphering the Old Man’s handwriting, Illya could read it with little effort. The résumé recorded the usual facts – date of birth, date of joining UNCLE, Survival School score, handgun rating and so forth, and then went on to describe Phelps’s career, the various affairs he had been involved in and their outcome and the positions he had held within the organisation. Now that was odd – Illya frowned at the picture. “I don’t remember Phelps,” he said. “No, you wouldn’t,” said Waverly gruffly. “He died in 1955, the year before you graduated from Survival School.” Illya looked back at the book in surprise, then turned the next few pages. From each, a black and white UNCLE agent looked back at him, sometimes smiling, sometimes serious, each with his own handwritten résumé. Seven pages in he found the first photograph he recognised – Paul Wescott, who he knew had died in 1964; but here in Waverly’s book he had enjoyed a flourishing career, albeit with some diplomatic ups and downs, ending as head of the Bolivian secret service. Illya raised an eyebrow at Waverly. “Did you do this for all of them?” he said. “No. Only the ones I expected to make a difference.” “And what are these biographies, then? The difference you expected them to make?” “Something like that,” said Waverly. “Futures I thought they might have had. Lives they might plausibly have lived. It seemed such a waste, you know, to have them end there. Cut down in the flower of youth, you might say. Or in healthy middle age in a few cases.” Unexpectedly moved by the idea, Illya opened a further page at random, and suddenly found himself the object of a profoundly familiar gaze. This particular young man wasn’t smiling exactly, his expression was much closer to a smirk, and he’d adopted a pose for the camera that was more suitable for a movie magazine than an UNCLE file, leaning forwards with one foot on a stool, his face half tilted towards the camera. Illya felt something cold clench inside his stomach. He didn’t want to read this résumé, didn’t want to know what career Waverly had envisaged for Napoleon, what kind of a life he might have led. And how ridiculous was it that after over quarter of a century he still found himself thinking that if only he’d been a little quicker that day, if only he’d found the staircase faster, taken the steps three at a time, then Napoleon might be living that life even now? He looked up to find Waverly gazing at him intently. “He would certainly have made a difference,” the old man said deliberately. Slowly, with hands that threatened to tremble, Illya closed the book, shutting away the past and a present that never was, and pushed it carefully away from him. “Did you write one of those for me?” he said, anxious to change the subject. Waverly chuckled. “The last time I checked you were still alive.” “But not exactly living the life you would have written for me.” “That’s true.” The old man’s smile faded. “I still don’t understand why you couldn’t have stayed with Section 2. We would have found you another partner eventually.” “But not one I could have trusted,” said Illya. “Oho, was that it?” said Waverly, “I did wonder. Trust can be earned, you know. It just takes time.” Illya said nothing. It wasn’t a topic he wanted to pursue. He had trusted Napoleon with his life, because Napoleon had trusted him. That was the way it worked. You put your life on the line when your partner was in danger, because that was the only way you could be sure that he would do the same for you. In a way, every time he saved Napoleon, he had been saving himself, guaranteeing that his friend would be there for him when he needed him, and vice versa, until their lives had become indistinguishable. But after Napoleon died he had never been able to bring himself to take the same risks for his new partners, because he had lacked that utter certainty that they would do the same for him. Oh, he had trusted them to make a reasonable effort, to do their best, but not to risk their all in the way Napoleon had, flinging all thought of self-preservation to the wind; and so he could not do the same for them, not unthinkingly. Men had died because of Illya’s hesitation. Good men. Men whose names and pictures and non-existent lives were doubtless now recorded in Waverly’s book, along with the differences they had never been able to make. Was it any wonder he had quit Enforcement? “Weren’t you ever tempted to write me a different life?” he asked, as lightly as he could. “One where I never transferred to Intelligence?” “No point,” huffed Waverly. “I’m quite sure that was a possible career path for you, along with numerous others, but the life you actually lived collapses all the other possibilities. Only the dead preserve all their potential lives intact.” Illya felt a rare smile well up in him. “I didn’t know you were up on quantum theory, Alex,” he said. “Well, I have to do something to keep my mind alive,” said Waverly testily, “even if the rest of me is dying by degrees. I can’t dash about like you young things so I have to settle for preserving what’s left of my mental agility. Besides, I don’t want to live wholly in the past.” “I’m only a young thing compared to you,” said Illya, “and I don’t dash about.” “No,” said Waverly with sigh, “Not any more.” He picked up the book and opened it. It was Napoleon again. Waverly must have looked at the entry many times for the book to fall open so easily at that page. “They shall grow not old,” he said, in the singsong tone of a schoolboy reciting poetry, “as we that are left grow old. Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. You know, when I was young, I used to find those lines a comfort. Then as I grew older, I thought it was nonsense, that aging was a small price to play for being alive. And now I’m in my dotage, I find myself starting to believe it again.” “Dotage is hardly the right word,” said Illya, rendered thoroughly uncomfortable by the confessional direction this conversation was taking. “I’d better be off now, Alex. There are a couple of reports I still have to look through. Is there anything I can bring you next time?” “No, no, I lack for nothing here, you know. Apart from youth, health and a reason for living.” Illya, appalled, couldn’t get out of the room quickly enough. He hadn’t intended to go back to his office, but work suddenly seemed a much more appealing prospect than sitting alone at home, trying to hold back the memories. For that reason alone, he thought, he probably couldn’t quit UNCLE. What else would he do with his time? He was almost relieved when a few days later he received a phone call from the Happy Vale Nursing Home saying that Alexander Waverly had passed away in the night.

10 May 1999 (Cliff Curtis) If you can look into the seeds of time (William Shakespeare, 1564-1616) I wouldn't say I regard myself as a guy favored by fortune. I worked long and hard to get where I am today, and I can tell you that making CEA had damn all to do with luck and everything to do with hard grind and an ability to take the long view. Besides, if fortune really did favor me, she wouldn't have saddled me with Kuryakin. According to official retirement policy, I should now be in my second blissfully Kuryakin-free year, and you know, just thinking that sends my blood pressure sky high. Of the last five suggestions I submitted for making UNCLE an organization fit for the 21st century, he blocked four before they even reached committee. You wouldn't think an intelligence nerd would have so much power, but the fact is George Dangerfield loves him to bits. Probably has a Cuddly Kuryakin doll he takes to bed at night. And Kuryakin can pull information out of thin air – he's nominally head of Section 4, North America, but I swear if a cleaning lady farts in HQ Mombassa, Kuryakin not only knows about it, he knows what she ate that put her bowels out of order. Combine that kind of knowledge with the ear of Number 1, Section 1 and you've got yourself a modern day eminence grise, and let me tell you that they're just as much of a pain in the butt now as they were in the days of the Three Musketeers. But not for very much longer. Because something really big has come up, something that, used right, will impact UNCLE's ability to defend our interests for years to come, and I'm damned if I'll let Kuryakin stop me. He's a wily old fox – used to be a field agent many years ago, and still hasn't forgotten the tricks he learned then – so I doubt the usual options will work, though I did put out a contract as a matter of routine. Call it Plan A. Plan A is neat and clean and won't leave any loose ends I can't tie up, but like I say, it has the disadvantage that it probably won't work. Which is where Plan B comes in. Plan B is everything Plan A isn't – complicated, messy, chock full of variables - but there is no way, no way on earth Kuryakin'll see it coming. And as a fringe benefit, it'll give us a chance to do a test run of the equipment.

11 May 1999 (Sam Parks) Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow (William Shakespeare, 1564-1616) My name's Sam Parks, and though I'm the youngest member of staff here at Section 4, I work directly for the Old Man. I'm proud of the fact, of course – there's a reason why it's pretty much the first thing I told you about myself – but the position is no sinecure. It's not that I don't have tremendous admiration for Mr Kuryakin, but to call him a slave driver would be an insult to overseers. He's also not too good at interpersonal relationships; I think his secret ambition is to be Mr Spock and not have to concern himself with pesky human weaknesses. His not-so-secret ambition is to get 32 hours of work out of a 16 hour day and to have every staff member in the section do the same. This sometimes collides with the aforementioned pesky human weaknesses, especially after a night on the town, but the Old Man has a point when he says lives depend on us extracting the right information from intelligence reports and that it won't be much comfort to the field agents who don't make it to know that our social lives are on track. And he doesn't demand anything from us that he won't do himself. For all that he's a couple of years past the official retirement age, he puts in longer hours than any human being should be able to manage, and he can winkle the key facts out of a report in less time that it takes to crack a nut, not to mention reading between the lines in a way that makes you think there must be some extra gen in there written in invisible ink only he can read. No, Kuryakin's got a mind like a razor, no question, and if you're not careful around him you'll get cut. He started working for UNCLE back when the Cold War was at its height, and it can't have been easy for someone with a name like Illya Nickovetch Kuryakin to rub shoulders with red-blooded Americans. I'm not sure he's ever actually been a godless pinko commie – well, maybe godless, but that's not exactly unusual in this business – because he keeps his political opinions firmly under wraps, for all that there've been mutterings from on high lately about just how loyal he is to the UNCLE organization. Not public mutterings, of course, but you don't get to be the Old Man's good right hand without having your ear to the ground and your eye on Section 1. I imagine Kuryakin's used to having his loyalty called into question by now, though, and it doesn't seem to affect him. But then, nothing ever does. So when the events I'm about to relate started up, it was like the sun rising in the West – something horribly, fundamentally, unoverlookably wrong, even though the rest of life carried right on as normal.

11 May 1999 Death be not proud, though some have called thee (John Donne, 1571?-1631) The anniversary of Napoleon's death was looming, and although Illya tried as always to push the memory from his mind, a cloud of lethargy descended upon him and eventually he gave up even the pretence of reading his reports and headed for home, picking up a newspaper on the way. He was unlocking his front door, struggling slightly with the key, since it had become curiously unwieldy over the last few weeks – doubtless an early sign of physical degeneration – when he heard footsteps behind him and a young man’s voice said uncertainly “Illya?” It was an intensely familiar voice, for all that he had not heard it for thirty years; so familiar, in fact, that he knew it must be an illusion. Apparently his brain was still playing tricks on him even after all this time. Grief was a funny thing. It made his heart pound in his chest as he turned to face the speaker, but when he caught sight of the man’s face, it hammered so hard that he wondered fleetingly if the next step in the process of decay was going to be a pacemaker. “Mr Kuryakin? Illya? It is you, isn’t it?” There was a degree of uncertainty on the handsome face now, a slightly self-mocking expression that flooded Illya with recognition, more so even than the voice. This was no mere coincidental similarity, this was a piece of his past stepped into his present, a ghost risen and made flesh. But even as his senses raced with exhilaration, his intellect urged caution, and Illya had always given his intellect priority. With a newspaper in one hand and his key in the other, he knew he would be at a disadvantage in going for his gun, so instead he said stiffly “Who are you?” “Look, I know it seems crazy, Illya, but it’s me. Napoleon. You must remember what I look like? Well, looked like, I guess I’ve changed a little since.” Judging by the expression on his face, he’d been going to add an unflattering comment about Illya’s own appearance, but instead he said “The damndest thing has happened. This is 1999, right? Well, do you remember Professor Bronsky? The mad German with the time machine?” “I remember. Napoleon and I destroyed the lab, so if you are trying to say -” “We did? That means I must get back after all!” For a moment the man’s face lit up with pleasure, then he noticed Illya’s forbidding expression and said “Look, all I know is that two days ago – well, it was two days ago to me, I guess it was a little longer ago for you - we were in Bronsky’s lab and then there was a strange noise and flashing lights and then here I was. I mean, not here exactly, because I was in the lab, but now. I was here now. In 1999.” Illya gave a very slight shake of his head. “It’s a nice story, my friend, very inventive, and I’m impressed by your research, but it never happened.” The young man with Napoleon’s face looked surprised. “Are you telling me you don’t remember the time machine?” “No, I remember the time machine, I even remember the flashing lights. I remember expecting something to happen, but nothing did. Napoleon didn’t vanish. Nothing happened at all. We finished the job, blew up the lab and left.” The young man frowned. “You sure about blowing up the lab? Because I didn't see any signs of an explosion. And I never said anything to you about the time machine sending me into the future? Huh. I guess I must have got back at the exact moment I left. And I must have had a reason for keeping it a secret from Ill - from you. Maybe I found something out here that prevents me from telling anyone when I get back.” He glanced swiftly around the deserted corridor. “It's rather public out here. Can we go into your apartment and discuss this in private? I swear I can prove to you that I’m Napoleon and I’m more than willing to give you my gun beforehand. I’m going to take it out now, all right?” Moving slowly, he reached into his jacket and pulled out – an UNCLE Special. Illya hadn’t seen one for years, but he recognised it immediately. A slight tremor ran through his hands as he dropped his newspaper and reached for it. It was heavier than he remembered, but the weight felt absolutely right, so much more reassuring than these modern lightweight things. A sharp tweak of nostalgia gripped him as he recalled the ethical sensibility behind its design. A gun that didn’t kill people – how absurdly sentimental could you get? “All right,” he said abruptly, “You can come in.” Presumably the weapon didn’t fire if its owner was willing to surrender it so quickly, but he kept it trained on his visitor just the same. Something flitted briefly across the man’s face - disappointment, Illya was sure. It seemed that after all these years he could still read Napoleon like a book; either that, or he was projecting expressions he remembered onto this oh-so-familiar face. He handed the other man the key, and watched as he turned it effortlessly in the lock. It made him feel old. Not that he hadn’t been feeling old anyway, what with Waverly’s death and the slowing down of his own body, but seeing this extraordinarily youthful Napoleon - or someone who looked just like Napoleon as he had last seen him – reminded him painfully of just how far he was from his own youth. The door swung open and the man glanced back at him. Illya gestured with the Special. “In you go.” Already he was running through his head a series of possible questions that only Napoleon could answer, but watching the man cock one eyebrow in mild surprise at how quickly he had conceded, he knew that he wouldn’t need them. This was Napoleon all right. And now that he was faced with him, across his tiny kitchen table, adorned with a bottle of vodka and two glasses, he discovered he didn’t know what to say, so he stuck to business. “How did you find me?” “I used my initiative, of course.” A charming smile – how absurdly young this man was! The skin beneath his two-day stubble was smooth, his eyes bright, his movements full of energy and enthusiasm. Illya found it hard to imagine that he had ever been that young himself. “All right, in actual fact I went to a public library and a delightful young lady showed me how to google.” A lascivious smile quirked the corners of his lips, as if he had uttered a double entendre. “It’s a good thing you’ve got such a ridiculous name – there still aren’t many Kuryakins in NYC and none of them are called Illya.” “Your own name isn’t exactly normal,” retorted Illya, annoyed. “Yes, but I thought it was best to look for you first. I didn’t know if running into myself was going to make the universe explode or something, and I didn’t want to cause the old boy psychological problems when his misspent youth suddenly turned up on his doorstep.” “That wouldn’t have been a problem,” muttered Illya, thinking aloud. Napoleon stared at him. Then his face softened in comprehension. “Oh, you mean I’m dead?” he said lightly. “When did that happen?” Illya regretted his remark. He hadn’t meant to be so tactless, but at some point Napoleon was going to have to know. “About thirty years ago.” Napoleon stiffened, his face whitening as he did the calculation. Clearly he hadn’t expected that – death in his late sixties must have seemed so far off as to be unreal, but death right on his doorstep, that was a different matter. “How?” he squeaked, then cleared his throat and tried again. “How will I – did I die?” Illya made a decision. He had several pieces of the puzzle here, but nowhere near enough. Napoleon, apparently, had made it safely back home. Two weeks later, he had died. Nothing in his behaviour back then had suggested he knew his death was imminent – if he had known, surely he would have done something differently? Not gone up onto the roof alone? Waited for Illya to arrive before firing? Telling him now might change the past, and Illya had no idea what the consequences of that for the present might be. Better to keep the knowledge to himself for the moment. And then a joyful thought struck him. “It doesn’t matter, Napoleon,” he said, his words tripping over each other in their eagerness to get out, “Because that is over now, your death is passed and you alive. You need never go back and so you will not die.” Napoleon’s face cleared as he grasped what Illya was driving at. “Right,” he said cheerfully, with all the confidence of youth. Sidetracked by the dreadfulness of his end, Illya had forgotten that cheating death had always been in the way of a hobby for Napoleon. “I can always google it anyway, if you won’t tell me.” “I hardly think you will be able to access UNCLE’s confidential files via google,” said Illya, “but I imagine you will have a lot of fun looking at porn sites while you try.”

12 May 1999 (Sam Parks) Nor dare I chide the world-without-end hour (William Shakespeare, 1564-1616) The first thing was that the Old Man came into work late. I know it doesn't sound like much, and you're probably thinking "Aw, c'mon Sam, there must have been the occasional late morning", but believe me, it just didn't happen. Ever. So there was already a bit of a buzz around the office when he finally did show up, and everyone looked at him extra closely, only you really didn't need to look that close to see that something was up. He looked – strange. He had rings under his eyes, like he hadn't slept, and he looked older somehow – no, I guess it's just that for the first time since I'd known him he actually looked his age. But for all that, there was kind of a – a thing about him, like he was doing handstands on the inside and trying not to let it show. But most shocking of all, he smelled ever so faintly of vodka. I don't know if I can convey just why that was such a kick in the teeth, except to say that if you got up to heaven and found God smelling faintly of vodka you might feel the way we did. Of course, we couldn't get a word out of him about why he was late - overslept, my ass! - and naturally we didn't dare ask why he looked so old or why he'd been drinking, so we all got our heads down for a solid day's work, and then nearly fell off our chairs when the Old Man announced just after noon that he was going home. This from someone whose idea of an early night is to knock off at around 10pm. The minute he was gone, I headed into his office to swap theories with Elsa, his secretary. Elsa is my ideal woman, a gorgeous, flirtatious lady with an acute insight into the human psyche. I'd marry her like a shot if she wasn't, you know, old enough to be my grandmother. "Maybe he's in love?" Elsa offered hopefully. "The vodka might have been to disguise the scent of perfume. Or maybe the vodka smell was perfume – Russian women aren't exactly subtle." "Right," I said, chuckling. "I can just imagine Kuryakin with some dumpy vodka-scented babushka pulling an all-nighter down at Vanya's Eatery." I think Elsa was slightly offended. She's as fond as anyone can get of the prickly old bastard, although she's dropped hints occasionally that they haven't always gotten along as well as they do now. "Why a dumpy babushka?" she demanded. "It might be some glamorous KGB spy. You know the type, all furs and "Darrrling." Someone out of his past. Someone he once truly cared about." I really, really wished she hadn't said that. Oh, not at the time. At the time I just laughed at the thought of anyone calling the Old Man darrrling, expressed the hope that he wasn't sickening for anything and seized the opportunity to go home an hour early myself, to prepare for a date with a young woman I was starting to get rather serious about. As it turned out, though, I never made it, because on the way home I got a message from Cliff Curtis that I was to meet him at Romeo's. Right now. And when Cliff Curtis says jump, I jump. Cliff Curtis is the bane of my existence, naturally. I don't even like the guy – he's too smooth, in a macho sort of way. Speaks in very short sentences. Has a kind of manly charm that ensures he always gets the best service in restaurants, and an irritating conviction that everyone is as susceptible to it as waiters and taxi drivers. But more to the point, he's my boss, or as I prefer to think of it, my line manager. See, the thing is, I work for Section 4 but I've got ambitions. I don't want to be stuck behind a desk forever, putting my love life on hold every time one of the Section 2 boys gets into trouble. I want to be out there myself, with Section 4 holding its collective breath while I perform feats of derring do, and women flinging themselves at my feet. And Cliff Curtis is Number 1, Section 2. In an unguarded moment – it's an open secret that he and Curtis are at loggerheads - Kuryakin once remarked to me that being CEA isn't the job it once was. I couldn't get him to elaborate, but I suspect he meant that back in his day the position was a lot more hands on, whereas now it's very much a matter of administration and policy development. I couldn't care less about that – my ambitions don't lie in that direction – but the point is that among other things Curtis makes the Section 2 appointments. And shortly after I joined UNCLE, Curtis sounded me out – said he liked to look over the newcomers to see if they're prospective Enforcement material and suggested he might pass a few minor missions my way to see how I shaped up. I pretty quickly figured out that what he meant was he wanted me to spy on Kuryakin and I told him where he could stick his "missions". I thought then that I'd blown any chance of making Section 2, but to my surprise Curtis just laughed – urbanely, of course – and said loyalty, like discretion, was an essential quality in a field agent and he'd be in touch again. Which he was, but although none of the other jobs he sent my way ever had anything to do with Kuryakin, I couldn't shake the uncomfortable feeling that I ought to tell the Old Man about it. Except that would have showed I lacked discretion, right? So here I was in Romeo's, hardly able to make out my boss's face in the dim light, gritting my teeth while he flirted with the waitress and showed off about wine in front of the sommelier. When he finally got down to business, though, I wished he'd spent longer polishing his image and left me a few more minutes of blissful ignorance. "OK, Parks, I know you're wondering why you're here. I'll put my cards on the table. Fact is, I'm worried about Kuryakin. You noticed anything odd about him recently?" Well, I could hardly say no, could I? Curtis clearly knew something was up, and if I denied it convincingly I'd look like a blind-deaf moron. And if I denied it unconvincingly I could kiss goodbye to my chance of making Section 2. "You mean like turning up late for work and going home early?" I said cautiously. "I mean like not acting himself," said Curtis, putting on a touching expression of concern. "He did seem a bit off," I muttered. "A bit off? C'mon Parks, your loyalty is beyond question, but just a mite misguided in this instance. We think Kuryakin's in trouble." "What kind of trouble?" "Look, I told you I was being up front with you. You're a good man, and a good employee, but right now I need you as an UNCLE operative and not as a Section 4 man. The information you want is classified A1 – top secret – and I can't show it to you unless I'm certain you won't go crying to Kuryakin. For his sake as well as UNCLE's. All I'm asking of you right now is that you agree to keep your mouth shut about anything discussed in this meeting. Then when you've heard what I've got to say, you can decide whether you want to be a part of it. But I can't give you security clearance until you agree to silence." He got silence all right, for a full minute, I estimate – and that's a long time when you're sitting in a restaurant with your boss breathing in your face – but I had to think through the situation first, and in the end I decided there was nothing to be lost by agreeing to Curtis's terms. Something clearly was up with Kuryakin, and it couldn't hurt to find out what. "All right, I agree." "Good man." Curtis nodded approvingly, and slid some photos across the table. "Recognise this fellow?" I scrutinized the pictures carefully, but failed to connect the rather blurred images with anyone I knew. "That one's Mr Kuryakin. Taken outside his apartment by the looks of it. The other guy – he's odd. Early thirties, I'd say. You don't often see a young guy with a haircut like that. Or wearing that kind of suit. He looks like he takes care of his appearance – cufflinks, see? - but his pants are too short." "You've no idea who he is?' "No, sir." I pushed the photos back over the table. "I've never seen him before." "Napoleon Solo." "I'm sorry?" "Napoleon Solo. We have several positive identifications. Oh, for Chrissake, what do they teach you youngsters? Solo was CEA of North America back in the 60s. Had quite a reputation – when I was going through Survival School he was still the guy whose scores you had to beat. But I guess that's ancient history to you greenhorns, huh?" "Um, but sir, if this Solo was CEA in the 60s, then this man can't possibly be him." "Of course he can't." Curtis positively beamed at me. "Solo was killed on May 30 1969, and it wasn't a fake-out, I had the body exhumed this morning to make sure. He's dead and buried all right. But the point is Kuryakin thinks this is Solo. And that means whoever is trying to get to him is doing a damn good job so far." "I'm afraid I still don't understand. Why would someone pretend to be a former CEA? And what's it got to do with Mr Kuryakin?" Curtis sighed. "You really should brush up on your history, Parks. Solo and Kuryakin were partners back in the day. A legendary team. Guess it just goes to show how long legends last these days, eh? Kuryakin quit Section 2 when Solo was killed. We don't know why. Maybe he felt guilty, maybe he just couldn't stand to work without his partner. Point is there was an emotional attachment there. And you don't need me to tell you how these things can be manipulated. Kuryakin doesn't have any other ties. Makes him a damn good operative. But someone's found a way to create a weakness. This guy with Solo's face shows up, Kuryakin falls for whatever cock and bull story he's been told, and the consequences are incalculable. Say, Parks, you're looking a little rocky. Let me get you a brandy." I was, indeed, feeling a little rocky. More than a little. It seemed ridiculous, outrageous, utterly bizarre, but a little thought showed that it could work. The major obstacle wasn't the technology, that was easy enough, but Kuryakin himself. Would he buy it? Could "Solo" put on a good enough act to fool him? Kuryakin was sharp all right, but he was also an old man, and he hadn't seen his partner in thirty years. The imitation didn't have to be perfect, it just had to be good enough. Good enough to keep the deception going once Kuryakin had swallowed whatever story Solo had fed him. And perhaps he wouldn't be all that hard to convince, not if he actually wanted to believe it. Poor old Kuryakin, it looked like maybe he was human after all. I felt a sudden stab of anger. "Who's behind it?" "We're not sure yet. That's why we need you, Parks. You're as close to Kuryakin as anyone gets. Keep an eye on him and this Solo fellow. Let me know the minute you find anything. And don't let him do anything he'd regret – you owe him that much. Do we understand each other?" "I think so. Sir."

12 May 1999 The time is out of joint; O cursed spite (William Shakespeare, 1564-1616) For all that running Section 4 was more a lifestyle than a job, Illya had retained his scientific curiosity, not least because it was important to keep up with the latest technological developments. As a result, he knew exactly who to consult on the tricky issue of time travel. It wasn't what you could call mainstream science, but he was acquainted with a promising young particle physicist at MIT who had coincidentally published a couple of theoretical articles in the field. On balance, he decided it would be better not to take Napoleon with him for the visit - he hoped to return with good news, but his innate pessimism warned him not to count his chickens too early; and besides, Dr Welch was both extremely good looking and an ardent feminist. Instead, he dropped a passing remark to the effect that he'd never noticed before just how much fashions had changed since the 60s, and left for the office and then the airport confident that Napoleon would spend the day shopping. Dr Welch proved as fascinated as Illya could have hoped by his story, but when he laid out his tentative theory that Napoleon could remain in the present, she turned fatalistic. “He has to go back, Kuryakin, because we know that’s what he did. He went back, in the past. That’s already happened, it can’t be changed. God knows what sort of temporal paradoxes it could give rise to if he doesn’t go back now.” “Temporal paradoxes? You mean marrying his own daughter, that sort of thing?” “No, no, that's not a paradox, that's just incest. A paradox arises when something that's already happened doesn't happen – they're acutely unstable. In the worst case scenario this whole timeline could just blink out of existence, because the prerequisites for unfolding the right way haven’t been fulfilled.” “Okay,” said Illya slowly, “So he has to go back. But he doesn’t have to go back right now. He could spend years here first. He could have a whole extra decade of life!” “That’s theoretically true. Since the future hasn’t happened yet, it’s not constrained to follow any particular pattern, as long as what happens fits in with the past adequately. But I thought you said your past self didn’t realise he’d been away?” “Yes, I had no idea until he turned up on my doorstep yesterday.” “Well, that means he can’t have been in the future for very long. I mean you would have noticed if he suddenly looked older or had a different haircut or different clothes, wouldn’t you? Can you remember noticing anything like that?” Illya thought desperately, searching for some tiny shred of memory that would prove Napoleon had been away for longer than a few days, but no matter how hard he tried he could find nothing. The blunt truth was that he had completely failed to notice Napoleon had been away at all, so he couldn't have been any different. Unless of course that was because he hadn't been away? "What if he came from another timeline?" "You mean a parallel universe? Well, there are certainly theories about branching temporal nodes that would allow for that, but it's never been mathematically proven. Whereas loops are really quite common – theoretically they occur every few centuries, it's just that no-one's ever picked up on one while it's actually happening. And they don't leave any traces, of course." “So you're saying I can’t change anything,” said Illya. “I can’t save Napoleon, I can’t even give him a few extra weeks of life. What’s the point of him being brought here if it doesn’t change anything?” “There doesn’t have to be any point,” said Dr Welch in surprise. “Solo triggering the time machine might have been pure chance. It doesn’t have to have some kind of cosmic significance. Maybe it was just an accident, a coincidence.” "Possibly," said Illya sourly, "but I don't believe in coincidences." "Fine, that's your privilege. But whatever you believe, I strongly advise you to find that time machine and get your friend back to where he came from as quickly as possible. For all our sakes. And then, if I may venture a personal ethical opinion, I think you should blow the damn thing sky high. God knows what something like that could unleash if it got into the wrong hands." Illya nodded gravely. "I have to agree with you there," he said. "Very well, I will take your advice. But not for 24 hours. Surely you will agree that 24 hours can't do any harm? You know, I regret now that I didn't bring Napoleon with me to meet you. Then I would have had the consolation of knowing that it gave at least one person very great pleasure to send him back."

12 May 1999 (Sam Parks) If you can fill the unforgiving minute (Rudyard Kipling 1865-1936) After the meeting with Curtis I headed straight back to HQ. Elsa was still hard at it, bless her, fielding Kuryakin's phone calls and generally making sure the place functioned in his absence. I hitched one hip onto her desk and got straight down to business – after all, time was of the essence here. "Elsa, you adorable creature, did Mr Kuryakin tell you where he was going today?" Elsa sighed. "No, he didn't. And before you ask, I have no idea where he went. And he’s not answering any of his phones." "He didn't place any suspicious calls before he left? Send any private e-mails?" "Who wants to know?" "I do. Look, Elsa, I think he's in trouble. It's not just the way he was acting today. Someone contacted me. I can't tell you about it, but it's serious, and I've got to find him before things get out of hand. Do you trust me?" She nodded. "Of course I do, Sam. And so does Mr Kuryakin. But I'm afraid he didn't trust either of us enough to leave any clue about what he's up to." Since intelligence-gathering clearly wasn't going to get me anywhere, I went back to my desk to do some hard thinking. What would I do if I were Mr Kuryakin? No, wrong tack, what would I do if I were Solo? Suppose I was an enemy agent pretending to be Kuryakin's dead partner, how would I try to worm my way into his confidence? That was easy enough – push his nostalgia buttons, get all those old memories flowing, till I had him eating out of my hand. For a moment I thought of pulling up the files on UNCLE's history, but it would take ages to find the kind of information I was looking for, and besides, I needed the personal touch, so I trotted back to Elsa's desk. "Elsa, you were at UNCLE when Mr Kuryakin was in Enforcement, weren't you?" "I certainly was. Snotty little fellow he was back then." "Suppose you were showing someone around who’d worked for UNCLE in those days? What would you take them to see?" Elsa blinked at me in surprise, then evidently decided that I had my reasons for asking. "Gee, where to start! Things have changed so much. I mean, did you know, the entrance to HQ used to be through a tailor's shop? You had to go into a little changing booth and pull a lever – it was terribly embarrassing for the female agents if there were any real customers in there, they used to have to pretend they'd been seized by an urgent need to check their nylons." I laughed at that. "A tailor's shop? You're pulling my leg, right?" "No seriously, it was a tailor's shop. Del Floria's, it was called. I believe it's a restaurant now. Vietnamese, I think." "Oh my God, that's it. Quick, Elsa, can you remember the name of the restaurant?” It was the work of a moment to confirm that Kuryakin had indeed booked a table for later that night. Since it was in an area I didn't know well, I figured I'd better get over there and stake out the place before he arrived. I was just heading off to fetch my trusty moped when Elsa called me back. "Sam?" "What?" "I know you can't tell me what kind of trouble he's in, but you will look out for him, won't you? I know he acts like he’s Mr Indestructible, but he's not." "I promise, gorgeous." The adrenaline was already pumping through my veins as I blew Elsa a kiss and hurried out into the night, feeling exactly like a field agent, with the world at my feet and a night of adventure ahead of me.

12 May 1999 Ah, fill the Cup: - what boots it to repeat (Edward Fitzgerald, 1809-1883) For all that he had agreed with Dr Welch’s conclusions, Illya found it unexpectedly difficult to relay them to Napoleon. Napoleon himself seemed willing to connive in helping him to avoid the topic, for all evening he kept up a flow of genial chit-chat about the wonders of 1999, the extraordinary political changes, and the abominable developments in men’s fashions. They wandered through a succession of bars, becoming progressively drunker and progressively merrier, until finally a taxi spilled them onto the pavement outside Kim’s. The slap of the night air must have had a sobering effect, for Napoleon clutched at Illya’s arm and said “Come on, Illya, I know it’s bad news or you’d have told me by now. I’m a big boy, I can take it.” Illya was suddenly struck by the absurdity of the situation. Standing here, outside Del Floria's, with Napoleon, as he had done a thousand times; and yet he was an old man and Del Floria's was now Kim's and only Napoleon was still himself, even if he did look slightly strange in his new suit. He struggled for the words, but they wouldn't come. "Yes." "You're right." "You have to go back." So simple, yet he couldn't find the breath for them. A saying from his childhood came back to him, a memory even older than Napoleon, and apparently just as unwilling to be confined to the past. "A word is like a bird; once flown, it can never be recaptured." "Sorry? You're not making a whole lot of sense, old friend." Oops, apparently he'd spoken out loud. Illya pulled himself together and was just saying "We still have a little time –" when Napoleon shouted “Down!" and barrelled into him. At the same moment he heard the unmistakeable crack of a rifle and found himself prone on the steps down to the restaurant with Napoleon on top of him. Another crack and a thud indicated that a second bullet had hit the door jam above their heads. With some difficulty he extracted his head from underneath Napoleon and squinted back at the road. "How many?" he panted. "Just the one, I think. That window up there. But if they knew you were coming here, there might be another one inside. Can you cover me?" "Only if you get off me, you great oaf." "Good." Napoleon started to rise, and then ducked down again as another bullet slammed into the door. "Persistent little bunny, isn't he?" Illya still wasn't entirely sure where their assailant was, his night vision not being what it had been, but he could see the window Napoleon had indicated and sent a long burst of fire in that direction. It seemed to work, for there were no answering shots as Napoleon raced up the stairs and onto the street. For a moment Illya wondered what the hell he was up to, then saw him skid to a halt beside a motorbike and bend over the ignition. "I've got to reload!" he shouted, and saw Napoleon bob down into cover behind the bike. One shot from the rifle bounced off a railing. The next went wide, or perhaps the sniper was shooting at Napoleon now, a suspicion confirmed when the familiar sound of an UNCLE Special rang out. Illya took a deep breath and ran as quickly as he could up the steps and over to the bike, scrambling onto the back with as much grace as he could muster. Napoleon had already swung himself up and with a violent lurch they took off down the road, Illya twisting round to manage a literal parting shot at the mysterious sniper. The bike leered crazily as Napoleon wrestled it round the next corner and then the next, zig-zagging through the backstreets in case they were being followed. Then, just as Illya's confidence that they had shaken off any pursuit approached certainty, a black shape appeared in the headlight directly in front of them. Napoleon wrenched at the handlebars and the wheels skidded out from under the machine. Men and motorcycle crashed unceremoniously into a pile of garbage cans. Poking his head out from under the pile, Napoleon said anxiously "Illya? Are you okay?" "I feel as if every bone in my body is broken. Wretched cat." But in spite of the soreness, he could feel something welling up inside him that was suspiciously like glee. How he had missed this, the thrills and, yes, the spills of active fieldwork, the adrenaline kick that set every nerve tingling, the feeling of being fully alive. "Glad to know you're okay. And now are you going to tell me what that was all about?" Illya limped over to the side of the road, lowered himself painfully onto the kerb and started picking pieces of lettuce off his trousers. "Your guess is as good as mine." Napoleon frowned. "In that case, for a head of Intelligence, you're remarkably ill-informed."

12 May 1999 (Sam Parks) But at my back I always hear (Andrew Marvell, 1621-1678) I caught up with them after about two miles – I'd actually lost them after that last turn, and was whacking the handlebars in frustration, but the sound of garbage cans clattering across the road about a street away gave me renewed hope. I abandoned the moped and scrambled cautiously over an alley wall, flattening myself along the top when I caught sight of a small figure limping across the road towards me. Looked like Mr Kuryakin had survived the crash, which was something. So, unfortunately, had Solo, who was engaged in pulling the bike out of a pile of garbage cans. After that first quick glance, I slid hastily back down behind the wall and flattened myself against it. Luckily, sound carried very clearly in the night air. I could hear Solo call across the road to Kuryakin. "... you going to tell me what that was all about?" "Your guess is as good as mine." "In that case, for a head of Intelligence, you're remarkably ill-informed." "For a fancy dresser, you smell remarkably of fish." There was silence for a moment and then the sound of footsteps coming closer. I guessed Solo had joined Kuryakin at the kerbside. "Be serious, Illya. Who would want to assassinate you?" "Can't you ask me who wouldn't? It would be a shorter list." "All right, narrow it down to the top ten suspects." "A disgruntled employee, a disgruntled former employee, a disgruntled boss, a disgruntled foreign –" "Hold it, you don't seriously mean to say Section 1 is on your list of suspects?" "You need to lose your naivety, Napoleon. This is a more cynical age." "Must suit you down to the ground." "I am not a cynic, I am a pessimist. There is a difference." "Fine, you're a pessimist, and I can see how you could drive anyone to homicide, but why would Section 1 need to resort to that? I mean, I'm sure you do a hell of a job, but you're over retirement age. They could just terminate your employment with none of this mess." "I didn't mean to imply that the whole of Section 1 was out to get me. George Dangerfield, who is Number 1, Section 1, wants me in post till I drop dead in harness. But there are other elements with particular agendas, and I have dug in my heels over certain issues of late." "Stubborn Russian. You see what happens when you haven't got me around to take care of you?" "I have managed perfectly well for thirty years. It wasn't until you showed up that people started taking pot shots at me." I couldn't help but grin at that. Whoever was behind this Solo business might have discovered a potential weakness, but Kuryakin sure wasn't making it easy for them to exploit it. On the other hand the conversation was taking a turn that made me distinctly uncomfortable. It was quite obvious from what Kuryakin was saying that he suspected Curtis was behind the assassination attempt. And if Kuryakin was right about Curtis, then where did that leave me? I sure as hell didn't want to be involved in any kind of operation against him, so maybe the right thing to do was just sneak away. Oh, come on, said the voice of reason, you can't give up just like that. What about this Solo creep? - Yeah, sure, said a second voice, that sounded just as reasonable as the first, and what if he's part of Curtis's set-up? After all, he was the one who put you onto Solo in the first place. - All the more reason to keep an eye on him, said Voice of Reason #1. – Kuryakin'll kill me if he finds out, said Voice of Reason #2. - Darling you've got to let me know/Should I stay or should I go? chimed in an altogether more frivolous part of my mind. - Oh shut up, said Voice of Reason #1. – Shut up yourself, said Voice of Reason #2. The debate was getting really heated, and I have to admit that it was distracting me somewhat from the task at hand, because I can't see how else I managed not to notice Solo until I felt the muzzle of his gun against my head. "Well, well, what have we here?" he said nastily. "Another little jackal?" There was a scrabbling sound, accompanied by heavy panting, and then Kuryakin's head appeared over the wall. The double-take he did when he saw me would have been funny if the situation hadn't been so humiliating. "Parks?" he said. "Yes, sir. Um, I can explain," I said, in a tone that even Forrest Gump would have found suspicious. "Really? I'm all ears. But just let me get down from this wretched wall first." "Not to worry, Illya," said Solo. "We'll come back over. You first, Parks, and don't try anything clever." "I don't think I'm capable of anything clever," I said dolefully, and scrambled after Kuryakin. He was waiting for me on the other side with his own gun drawn and I thought then that I'd finally blown it for good. Solo swung down after me with far more elegance than any man covered in reeking fish heads has a right to display. "Are you going to introduce me?" he said. "This is Sam Parks, one of my men. Perhaps you'd care to tell me what you were doing hiding behind a wall listening in on one of my private conversations in the middle of the night, Parks?" It's moments like this that test a man. Not to put too fine a point on it, being caught lurking behind a wall right after someone had made an assassination attempt on Mr Kuryakin didn't look good, and telling the truth wasn't exactly going to put me in his good books either, not after what I'd just heard about Curtis. On the other hand, since it didn't look like I was going to be in his employ longer than the next five minutes, this was shaping up to be my only chance to warn Kuryakin about Solo. I figured I was going to have to bite the bullet and admit to having been suckered. Kuryakin didn't take it any better than I expected. "Since when does Curtis contact you when he wants someone tailed?" "He didn't ask me to tail you, sir. He just asked me to keep an eye on you. Stop you -" I tried to swallow, but my mouth was completely dry – "stop you doing anything you might regret, sir." "And why did you think I might have cause for regret?" "Because he told me about – him." I was a bit nervous about making any sudden hand movements, so I gestured at Solo with my elbow, coincidentally making eye contact. I took the opportunity to glare at him, but he merely inclined his head slightly in return, the gun in his hand never wavering from my temple. "Please sir, you must realise this can't really be Napoleon Solo. Whoever it is, you're being duped." Tact isn't my strong point, but even I realised that I hadn't expressed myself too advantageously there. Fortunately, Kuryakin didn't seem to notice, for instead of reacting to what I'd said, he looked over at Solo and said "You only found me last night. Curtis seems to have remarkably good intelligence." "He had your apartment under surveillance, sir." Both of them looked at me. "Maybe," said Kuryakin, in the tone of someone humoring a kid, then he turned back to Solo. "Do you think you could have been followed?" Solo shrugged. "I can't say looking out for a tail was at the forefront of my mind. It's possible." "If you were followed, it would mean Curtis must have known where and when you were due to arrive. And that suggests..." "That he may have been the one to program the time machine," Solo finished for him. "There are some very nasty worms wriggling out of this can, Illya." This was too much. Tact be damned, I found myself almost yelling at Kuryakin. "Sir, please, this is ridiculous, I understand why you want to believe this is your friend, but for God's sake, he can't even pronounce your name right!" To my intense frustration, they once again exchanged glances, as if this were some sort of non-verbal code. Then Kuryakin said drily "Napoleon never could." "I think I pronounce your name just fine. Now tell me, Parks" – the bantering tone had suddenly gone from his voice – "how did you find us?" Suddenly my big espionage achievement didn't seem all that great. I shuffled my feet miserably and said "It was a guess really. Elsa said Kim's used to be the entrance to UNCLE HQ, so I thought maybe you'd make a trip out there, for old time's sake." "Did you arrive there much before us?" "Couple of hours. I wanted to check the place out first." "That's it, then," said Napoleon confidently, "They tailed him. A couple of hours would give our sniper pal plenty of time to get set up." Kuryakin sighed. "I think," he said, "that we had better go and check out whatever remains of Bronsky's lab. Something tells me that we will find the answers we need over there. I'll get a cab. And you had better shower and change first, Napoleon. I don't think it's safe for you to stay in the present much longer, and I'm quite sure I'd remember if you had come out of Bronsky's lab suddenly smelling of fish heads. And you'd better come with us, Parks. I don't want Curtis picking you up without me to look after you." I guess Kuryakin was afraid they had a tap on his cell phone, because he limped off round the corner to hail a cab in person. That left me and this Solo character to keep each other company. I have to admit, I was a lot less sure than I had been that the guy was a fake. The way he and Kuryakin acted around each other you could tell they had the silent communication thing down pat, and I don't see how you could teach an impostor to do that. And then there was this time machine Solo had mentioned – Kuryakin clearly knew what he was talking about, so maybe there was an actual scientific explanation for how he got here. I stole a sideways glance at Solo. He didn't look like a top Enforcement agent, the one who set the standards everybody else had to meet. He looked like a movie star. A vain movie star. Not the kind who plays James Bond, though. Those guys are all about 6 foot tall and have rippling muscles, and Solo was on the small side and actually looked like he was kind of skinny under his suit. Not as small and skinny as Kuryakin, but definitely not Pierce Brosnan either. Yet he and Kuryakin had once been UNCLE's crack team. Legendary, Curtis had said. And for all that it was easier to imagine Solo primping in front of a mirror than punching out a bad guy, he had certainly reacted quickly enough when the sniper struck. I tried to imagine him with a younger version of Kuryakin, a less wrinkly and less gray version, but my brain stubbornly insisted on producing nothing but images of the Kuryakin I knew. And I really couldn't see him in a stand-up fight. "Hey, do you mind if I ask you something? What was Mr Kuryakin like when you knew him?" Solo raised an eyebrow at me, but he didn't look perturbed by the question. Actually, he gave the impression that most things didn't stand a chance of perturbing him. "Illya?" he said. "Not that different from how he is now. Cranky. Stubborn. Strange sense of humor." "It's kinda hard to imagine Mr Kuryakin as an Enforcement agent. I mean, he's not what you'd call powerfully built." "True, but what he lacks in weight and reach he makes up for in enthusiasm." Solo must have caught an element of skepticism in my expression, because the corner of his mouth twitched slightly and he added "Get him to demonstrate the human cannonball technique some time, it's surprisingly effective." "Human cannonball technique?" It was shaping up to be an intriguing conversation, but unfortunately that was as far as my oral history project got, because at that moment Kuryakin arrived back with the cab.

13 May 1999 Distant footsteps echo (Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1807-1882) The site where Bronsky's lab had been was now occupied by a lingerie store. Illya thought fate could hardly have provided Napoleon with a more suitable entry point to 1999, and judging by Napoleon's smirk, it was a view he shared. Under the circumstances, it seemed highly suspicious that the storeroom of the new building still housed a trap door. Levering it up revealed an elderly metal spiral staircase that wound down into the darkness. Napoleon produced a flashlight and led the way, treading cautiously so that his feet didn't clang on the metal. As the beam of light raked over the walls, Illya felt a shiver of memory run through him. It wasn't instant recognition, as when he had first heard Napoleon's voice, but the rough stone walls triggered a sense of familiarity. Strange to find a cellar in New York with stone walls. He remembered now that there had been a concealed door at the far end of the room; he had burst through it after setting the charges, tripping, in the urgency of his flight, at the foot of the staircase, and Napoleon had pulled him up. The musty smell, on the other hand, didn't unleash any particular associations. Illya supposed he had been in too many dank, mildewed underground rooms for the smell to seem anything other than generic. Treading softly, they gathered at the wall at the far end, where Napoleon silently counted slabs until he found the right one and pressed against it hard. The door creaked open with a horrible groan that made both him and Illya jump round to see if anyone had heard, but the cellar remained indifferently dark and silent. The next room was the lab. Illya found and flicked the light switch, and a single neon light strip stuttered reluctantly into existence in the centre of the room. He couldn't suppress a sharp intake of breath. He remembered this room all right. It wasn't very large – the lab had been a private madman's private folly – but every available inch of work space was crammed with equipment. Most of it consisted of computers, of a kind Illya hadn't seen for years - enormous grey metallic things that stretched up almost to the ceiling, adorned with impractically large buttons and little coloured light bulbs that would doubtless flash importantly during operation. The time machine was nowhere to be seen, and he remembered now that it had been hidden away in a room of its own, shielded from the rest of the equipment. It felt beyond strange to be standing in this place that had changed so little in thirty years. Illya had a sense that his past and Napoleon's future were converging, separated now only by the thinnest of membranes. In how short a time would Napoleon be racing out of here, dragging Illya up the spiral staircase, just as he so vividly remembered? Dragging him out of here, but apparently at unnecessary speed, given that there was no sign whatsoever of an explosion. For all the decades of dust that had settled over the equipment, it radiated an insolent intactness that seemed calculated to rub Illya's nose in the failure of his incendiary skills. "I don't understand," he said, "The explosives should have blown up the entire lab." "Well, it's still here," said Napoleon. "You must have done a second-rate job." "Hardly," said Illya. "More likely is that you sabotaged them after I had laid them, knowing that you would one day need the time machine to get back to 1969." "You're just trying to shift the blame onto an innocent bystander." "Doesn't look like anyone's been using it recently," Parks said, running his finger over one of the work surfaces. "I'm not an archaeologist but I’d say this is half a century's worth of dust." "Surprisingly clean floor, though," said Napoleon meaningfully. He gestured with his gun towards a door at the far end of the lab and mouthed "Time machine." Illya frowned. Of course Napoleon wasn't winding him up, he didn't know himself whether the charges had failed or whether he had sabotaged them. That all still lay in his future. But his own pride was nonetheless piqued. Glancing round the room, he tried to remember where he had put the explosives – where would they have done maximum damage?

13 May 1999 (Sam Parks) What if this present were the world's last night? (John Donne, 1571?-1631) Walking round that lab was like strolling through a living history museum. I once saw a picture of a really early computer. It was called, and I kid you not, "Spring Breeze", and it took up an entire room. This place was like that – there weren't any separate workstations, it was all one gigantic computer. There was even a machine that punched holes in card to give the read-out. But I didn't get long to look at it, because Solo was leading the way to a metal door tucked in between two rows of tiny monitors. There was a big blue button next to it, but since the electricity wasn't switched on, pushing it did no good. Solo fumbled in his pockets for a moment and brought out a small rectangle of yellow plastic, a bit like a credit card, which he inserted into the crack between the door and the wall. He ran it up and down a few times and then there was a click and the door swung open. "So much for security," I said. "I guess Bronsky's genius lay elsewhere," said Solo with a wry smile and stepped through the door. And there it was, the amazing time machine. It looked like nothing so much as a giant carrot, if carrots were made of clear plastic and had lots of colored tubing inside. To be honest, it wasn’t that impressive. It looked more like a kid’s toy version of a time machine than an actual one, and it was standing on a circle of rather lurid linoleum – lime green has never been my favorite color – but other than that there was nothing in the room. "Now if I recall correctly," murmured Napoleon, "I was standing on that attractive bit of flooring when the light display started, and Illya was not, which suggests that it marks the radius of influence within which the machine works. So don't step on it." "I wasn't going –" I began indignantly, when a horribly familiar voice said from behind me "All right, gentlemen, hands on your heads." I was quite sure it was Curtis before I even began to turn round, but my stomach still plunged like an out-of-control elevator when I saw him. He was not, however, sporting the expression of triumph I expected but instead looked rather annoyed. "Where's Kuryakin?" Believe it or not, that was when I first noticed that Mr Kuryakin wasn't in the room with us. I guess I really wouldn't make a very good Enforcement agent. Solo, however, seemed entirely unfazed. "Mr Curtis, I presume?" he said. "Illya's not here. Someone had to stand watch outside." "Don't play games with me, Solo," growled Curtis, "I know damn well he's here. We saw you all come in." "Perhaps you should consider changing your optometrist," said Solo. "Ha ha, very funny, I'm pissing myself. Tell me where he is, Solo, or so help me I'll shoot you where you stand. And get away from that machine." Curtis wasn't the only one with a weak bladder. I was shaking like a leaf myself as I walked back into the lab, and my nervousness only increased when I saw that Curtis had brought a prime piece of back-up muscle along with him. So much for my brief, crazy idea of jumping him. Solo, however, was as unruffled as ever. "You can't shoot me, Curtis," he said calmly, "if you kill me you'll break the temporal loop. I won't go back, the past won't be able to happen the way it did, and this whole timeline will collapse." "So what?" said Curtis, "So we'll have a past where Napoleon Solo disappeared during the Bronsky affair. Can't see that that'll make much difference to how history turns out." "Can't you? It may not seem much of a difference to you, Curtis, but it's still not what happened. You kill me now and this whole timeline will be replaced by a different one. Millions of people will cease to exist. Including you." "You mean millions of people will never have existed. And you can't kill someone who's never existed. I'm sure some version of me will still be around, and if not – well, I reckon it's worth the sacrifice. Think about it, Solo – the power that machine will give UNCLE! We'll be literally undefeatable!" "Those people do exist, Curtis. They exist now, and if you –" "Oh, turn off the bleeding heart, Solo, we haven't got all night. Now for the last time, where's Kuryakin?" "Here!" said a voice from above our heads. Involuntarily we all glanced upwards – all except Napoleon, whose right foot shot up and knocked the gun out of the goon's hand, even as Kuryakin launched himself from on top of the computer right onto Curtis. Curtis crashed over backwards, his gun firing as he fell, and hit the floor with a loud "Oof!" Kuryakin rolled off him and I dived for the gun, trying to wrest it out of his hand before he came to enough to aim it. Unfortunately, Curtis is built like Pierce Brosnan, and for all the air had been knocked out of him, he recovered enough to grapple with me. My attention was 100% on the gun, so I never saw his left fist coming, but as I scrambled groggily up, spitting out blood, I saw Napoleon fire. Curtis jerked and fell backwards and Napoleon fired again, then spun round and shot the goon, who toppled back against a work bench and slid slowly to the floor. And that was that. With a little effort I made it upright and looked around for Kuryakin. He was still lying curled up on his side, but when I went over to him he unrolled and struggled to his knees. "Are you all right, sir?" I asked. "No, said Kuryakin testily, "Next time, remind me that I'm too old for this sort of thing." I glanced at Napoleon and realised that for once it was my eye he was trying to catch. "Human cannonball?" I asked, and he grinned. "Human cannonball." "What?" said Kuryakin irritably. "What are you two on about?" "Tell me, Illya," said Napoleon, "how come you weren't by the time machine with us?" To my astonishment, Kuryakin twitched guiltily, like an employee caught with his hand in the cash register. "Oh, that," he said. "Um, well, I couldn't believe I hadn't laid the charges properly, so I crawled under the bench to check, and that's when Curtis came in. And I was right, Napoleon, look!" With a flourish, he produced a small black plastic box from his coat pocket. Three thin colored wires were dangling rather pathetically from it. "Sabotage!" he said triumphantly. After that there was a rather difficult silence, which went on for so long that I had to repress some serious urges to shuffle my feet or cough. I guess my insight into the human psyche is nowhere near as acute as Elsa's, because it wasn't until Solo said "Shall we –?" and Mr Kuryakin simultaneously said "I suppose we'd better –" that I realised they were trying to work up the nerve to say goodbye to each other. I'm not sure how much longer it would have been okay for Solo to stick around without, you know, endangering the existence of the entire world, but I guess they wanted to play it safe. Or maybe it's like at the end of a holiday, when you've already packed and could theoretically spend the last couple of hours sight-seeing, but in the end you decide you might as well go straight to the airport and wait there. Better to get it over and done with than watch the end loom ever nearer. So we headed back into the time machine room, and Kuryakin found the switch that activated it. The thing lit up like a Star Trek generator, and a low level hum started up that didn't seem to come from anywhere in particular but gradually filled the whole room. Solo shook my hand and said "Nice to have met you, Sam. It's good to know the future of UNCLE is in capable hands." I was so taken aback at the compliment – or maybe he was being sarcastic - that it was all I could manage to stammer "Goodbye, sir," but I don't think he noticed, because he'd already turned his attention to Mr Kuryakin. For a moment they faced each other, saying nothing, then Kuryakin suddenly stepped forwards and put his arms around Solo. That, let me tell you, was my single most embarrassing moment in a night already filled with choice humiliations. I was so obviously watching something intensely private and intruding on a moment that could never be repeated. It had never really hit me before that Solo was dead – that these two were finally getting to say the goodbyes they'd never managed the first time around, and here was me, standing right next to them like a great big lemon, feeling like I was taking up all the space in the room. Since the ground resolutely refused to open beneath my feet and swallow me up, I did the next best thing and tried very hard not to move or breathe or do anything at all that might draw attention to my presence. For a moment they just stood there, frozen like a statue. Age embraces youth, or something allegorical like that. Mr Kuryakin said something to Solo, which, thank God, I couldn't hear, and Solo nodded. Then Kuryakin dropped his arms, and Solo turned to face the time machine. In a gesture that seemed completely automatic, he smoothed down his hair and straightened his tie. Then he stepped onto the circle of green. There was flash of lights and a weird howling noise and then he was gone. Kuryakin took a deep breath. "Better get those idiots in there handed over to Dangerfield. This is going to mean months of paperwork." "Handed over? You mean the bodies?" Kuryakin looked at me and his eyes were bleak. "Oh, they're not dead, Sam. But you couldn't be expected to know that. UNCLE doesn't issue Specials anymore."